Article by Joan Crystal Pearlman

Text and photographs by Joan Crystal Pearlman

The spark of appreciation for folk art has been ignited in Mella, a village in the southeast part of Cuba. There, the Grupo Bayate — eight self-taught artists who have banded together for spiritual and economic support — has discovered that working together fits their needs both as artists and as modern Cubans.

Working as a collective is part of the political revolution, but it is also a longtime Cuban tradition. It makes sense economically in a time of scarcity to share art materials and even gasoline to transport art works to exhibitions. Also, there is a better chance of a group’s getting exhibition space, town support and recognition. Above all, these artists enjoy working as a collective to preserve cultural values. First, they say, they want to be a link between their community and the outside world in a non-commercial way. But the continuing economic crisis makes it important that they promote and sell their work.

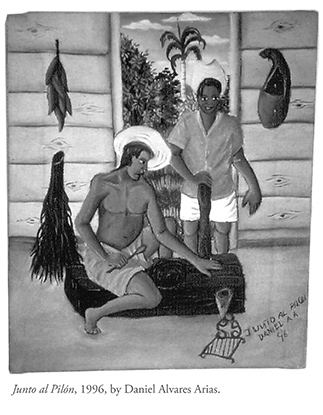

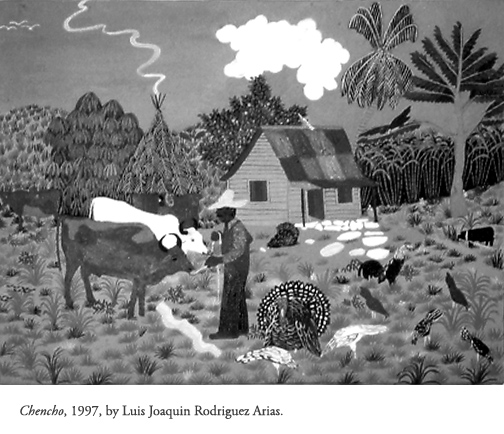

A leading member of Grupo Bayate is Luis Rodriguez (Luis Joaquin Rodriguez Ricardo), a former construction worker who paints from his experience and his heart. Through his depictions of the Cuban countryside he opens a window to the daily activities in his village, Mella, and perhaps to his soul as well. Others in the group include his father, baker Luis Joaquin Rodriguez Arias; driver Roberto Torres Lameda; fisherman Rolando Alvarado Lamorout; photographer Luis Alberto Villalon Rades; physician Felipe Reyes Merino; policeman Angel Yopiz Martinez; and accountant Daniel Alvares Arias. Luis Rodriguez’ wife, Luisa Maria Ramirez Moreira, is an art historian who writes about the Grupo.

Most of the artists in the Grupo Bayate are in their thirties, born about the time of the Cuban revolution. Although their styles are individual, their work is linked by a common subject — village life. They also have in common an unpretentious presentation, detailed ornamentation, vivid color and a narrative aspect.

Luis Rodriguez, the most recognized in the group, has had one-man exhibitions in Santiago de Cuba and in Oxford, Miss., at Southside Gallery. In 1997, the Grupo took part in an exhibition in New York City organized by the Center for Cuban Studies.

In Rodriguez’s work, the viewer becomes privy to the simple stories of everyday life — baseball games, a train chugging through a village, daily food preparation. However, some spirited paintings hint at a life in flux. The sense of turbulent activity is achieved with the use of diagonals, a vibrant palette and angles replacing curves. These active paintings are in strong contrast to the serene demeanor of Rodriguez himself.

Other paintings by Rodriguez draw on memories of the voodou ceremonies that he often witnessed during his childhood in the tiny town of Paso Estancia. Most of the town’s population had emigrated from Haiti, and Rodriguez’s neighbor was a Haitian priest/healer. In one of these paintings, four men lift a table with their teeth while a celebrant atop the table whirls to the clapping and cheering of onlookers. The sense of movement, sound and rhythm is heightened by brilliant colors punctuated with graphic darks and lights.

When asked whether he considers not having attended art school a disadvantage, Rodriguez replies, “No, it is an advantage.” He explains, “It is because the spontaneous, natural flow of naive art allows me to express sentiments freely without worrying about technical knowledge that could limit ways of reflecting feelings.”

While Rodriguez draws inspiration from his life and the landscape around Mella, he is quick to say that his most important inspiration and source of encouragement has been his father, the original founder of Grupo Bayate. In homage to his father, Rodriguez signs his work, “El Estudiante.”

The father, Luis Arias, designated leader of the Grupo, was not able to go to art school and, unlike his son, perceives this as a loss. “There is so much to learn,” he says. “Talent is something people are born with, but no one in his own life can accumulate the knowledge that humanity has accumulated throughout history.” Arias thinks his art is particularly Cuban because “I was born here and have loved here. I don’t know if there is anything that distinguishes Cuban art from others except that what I paint I do with my soul, and because of that I consider it sincerely Cuban.”

Rolando Alvarado Lamorout, the fisherman, says that being born with the sensitivity to appreciate the world is better than any school. “I paint what motivates me with no commitments to anyone but myself,” he says.

The artists agree that much of what is Cuban about their art is reflected in their depiction of Cuban life. “Our art is Cuban,” says Felipe Reyes Merino. “It is our landscape. None is more beautiful.” They all say they would like more art materials and more time to make art, but their main aspiration is to have the Mella style recognized and appreciated.

Grupo Bayate states in its manifesto its overriding goal: “To stimulate and maintain values of naive art in the region as well as to recapture its artistic traditions, and to facilitate an exchange with all who are interested in working in and promoting this art.”

In the tiny Cuban town of Mella, real value is put on the qualities of a direct, untutored style. This validation of the style, as well as recognition of its fragility, is amazing in that since the 1958 revolution in Cuba, all education through graduate and professional levels is free and encouraged. There is no government imposition of an official style, such as social realism. When someone is recognized as having artistic talent, he or she is sent to art school, if possible.

Cubans, as a whole, are introspective about their politics as well as their art. They have tried to overcome isolation in the international art world by keeping abreast of trends. Partly because of this, self-taught art has not always been highly regarded.

How can we account for the success of the Grupo Bayate and the pride its members take in their work? One reason may be related to the economic necessities brought about by the double setbacks of the tightened trade embargo and the collapse of the Soviet bloc, which resulted in a renewed appreciation for the simpler ways of doing things. Adversity has brought with it the challenge to be “low-tech,” which is reflected in the increased use of bicycles, alternative medicine and ecological farming. The counterpart to these measures may be an increased respect for an art which returns to the basics.

Cubans are searching for their roots and for their own expression. Grupo Bayate, with its visual descriptions of a simpler life, gives viewers an opportunity to share their expressive vision of a simpler Cuba. As Santiago artist Suitberto Goire has written about the Grupo Bayate, “They bring with them a soft breeze, the smell of wet earth and the sweetness of sugar. . . . We are always grateful to them.”

JOAN PEARLMAN from New York City, has taught at N.Y.U., The New School and the American Folk Art Museum Institute. She recently participated in a two-person exhibition of her photographs in “Woods Hole Women of a Certain Age.”

As seen in the Folk Art Messenger: