Article by Judith Meyerowitz

All paintings by Nellie Mae Rowe, courtesy of Brooklyn Museum and High Museum of Art.

The exhibition, Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe, on view from September 2, 2022 to January 1, 2023, in the Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, originated at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, which has a gallery devoted to her work.

What would Nellie Mae Rowe think about the title of this exhibition and its location alongside Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party? She lived through the Feminist and Civil Rights movements – tumultuous times for women and Black people. Through extensive informative labels, the Brooklyn Museum invited visitors to appreciate her life as much as her art. During her 82 years (1900-82), Rowe experienced a century in transition. The more than 100 works on display represent a major retrospective of her work compressed into the last 15 years when she was active as an artist. The museum exhibition helps us put together the story of the person and the period. It describes her creative goals as a demand for “respect and visibility” as a Southern Black woman and as “a form of self-care.”

Rowe created a body of work that fills several gallery spaces with colorful, primarily pencil and crayon drawings, on everything from ledger paper to cardboard. Much later she was represented by Judith Alexander’s gallery, which purchased her art and allowed her to afford other materials with which to experiment. Her work is not completely new to the Brooklyn Museum. Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980, a 1982 Corcoran Gallery of Art exhibit, included Rowe and traveled to the Brooklyn Museum shortly before Rowe’s death.

Born in rural Fayette County, Ga., Rowe was the daughter of an enslaved sharecropper. There were ten children, nine girls and one boy, and she was the second to the youngest. She said in an interview that “My mother was born the year of freedom…. the year they freed the blacks,” and Rowe is thought to have chosen July 4th as her birthday. She clearly had a sense of history. In 1930, she moved to Vinings, Ga., a community that would become part of the larger Atlanta urban area.

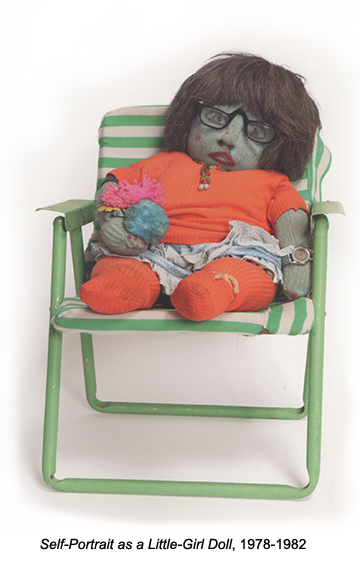

Rowe was a woman who grew up working in the cotton fields, who left home to marry at 17 and then married again following her first husband’s death. She was a woman who did domestic work throughout her adult years, until she freed herself in her 60s to develop her artistic identity. She became freed not only from taking care of others but free, as the museum information says, “to reclaim” the little girl who only wanted to draw and make dolls.

At the death of her second husband, Rowe is quoted as saying: “My husband died in ’48, and I ain’t been bothered with marrying or cooking since then – Whew, child, I couldn’t stand it.” She is also to have said: “I kept house long enough. I don’t want to be bothered by nobody ‘cept self.” It was now time to create not only art but also her own identity. Looking back at her childhood, Rowe said: “When I could have been learning how to draw, I had to go into the field. I didn’t have the chance people have now.”

The drawing, Real Girl, 1980, from the High Museum collection, is one of a dozen paintings in which photographs of herself appear. Her signature is in the center of the heart like a valentine done by a girl in childhood or reminiscent of a sampler. Flowers and color choice also give a girlish feel as does her pose with an almost life-sized doll. The museum suggests that it is a “valentine to herself.”

When I was a Little Girl, 1978, expresses the conflict between childhood enthusiasm to draw and display her art and an ambivalent reaction from her mother who is depicted as both a punisher and a rewarder, while another version of Rowe appears to float freely above. Perhaps it was healing for Rowe to revisit herself as a young child. In a 1982 taped interview with Judith Alexander, her gallery representative, collector and friend, she said: “I see people crippled and I may draw them to ask the Lord to help them. Nothing I draw I draw to make fun of. I draw what I see of people’s condition, and I ask the Lord to help them.”

Rowe declared to a reporter in 1979, “I am Black, and I love my Blackness.” In the 1978 drawing, Peace, we see a birds-eye view of two large Black hands in the foreground covering perhaps two-thirds of the painting, with pastel colors in the background. The viewer is enveloped by them. Are they raised in prayer or as a blessing?

The disappearance and murder in 1979-1981 of nearly 30 primarily Black Atlanta children and adolescents was a subject of another Rowe work. She also kept a picture of Martin Luther King, who preached in Atlanta, just 20 minutes away from Vinings. The March on Washington came shortly before her own declaration of independence when she would fulfill her own dreams.

In the same taped Alexander interview, she said: “My daddy lived in slavery times. He would sit down at night and tell us children, ‘I have no energy to draw pictures of slavery times. It makes me sad. You must not think back to those times because these are new days.’” Not only does this suggest that Rowe was quite aware of how the history of slavery had affected her family, but also that she lived with the optimism reflected in the colorful, Chagall-like wonder of her art.

Rowe lived her art literally as well as figuratively. She created a world of dolls made by hand, a collection of found-objects, sculptures from chewing gum, and hundreds of drawings that were part of her “Playhouse.” There was no boundary between home and studio nor between life and art. Yet it wasn’t a world in which to retreat. It drew attention and picture-taking and visitors. Her grandniece in an interview at the High Museum said, “It was like her gallery.”

The Playhouse can also be understood within the framework of art environments found in the work of other outsider artists (such as in Howard Finster’s Paradise Garden). Sadly, the Playhouse was demolished after her death, but photographs remain. In the exhibition you could view the details of a re-imagined Playhouse constructed in the gallery. It mesmerizes the viewer as a childhood dollhouse might, while knowing it is more – identity, creativity, or possibly a gift of self-love.

In 1968, she returned to drawing and started decorating her yard. The Playhouse seemed to have spiritual and healing meaning to Rowe: “I do what I want to do and what the Lord wants me to do,” she said.

Her deep spirituality appears in many drawings, such as her second husband’s passing through and crosses often next to the Playhouse. This is shown in her painting, Look Back in Wonder at How I Got Over, 1982. There are also suggestions of her awareness of local African traditional practices and beliefs in her use of “haint blue,” an indigo dye used in the South to scare “haints” or evil spirits. Decorating a tree with blue bottles hung upside down, a Congolese practice, was made for similar purposes.

There is a dreamlike quality to Rowe’s work. She said: “Things come to me in my sleep and sometimes I will get up in the night and make a start of what I have seen….I draw things you haven’t seen born into this world, but these things may someday be born but I’ll be through it.” This gives us permission to imagine and enjoy her fantastic creatures. What happens to the “dream deferred” of Langston Hughes? Sometimes it explodes in a burst of color, a wall of memories, a tree of bottles and an enduring need to create.

JUDITH MEYEROWITZ, a psychologist from New York City, has served as a docent at the Metropolitan Museum.

As seen in the Folk Art Messenger: