Article by Kyle Mancuso

Photographs Courtesy High Museum of Art

In March, George Voronovsky: Memoryscapes, an exhibition about the life and work of Ukrainian-born self-taught artist George Voronovsky (1903-1982), opened at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta and will be on view until August 13, 2023. Voronovsky’s dozens of paintings and sculptures were preserved for decades by Florida-based photographer and folk-art collector Gary Monroe who befriended and supported the artist in the late 1970s and early ‘80s. This art has been shown only a few times, meaning that every wall of the exhibition holds surprises for the visitor, folk art insider and first timer alike.

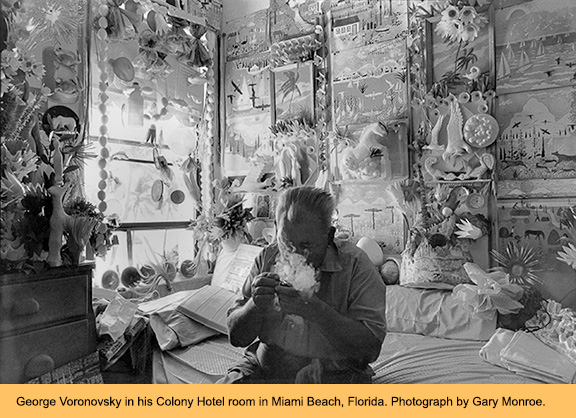

In the first gallery, a large black-and-white mural showing Voronovsky in his room at the Colony Hotel in Miami Beach is supplemented by hangings of his sculptures: tin and paper beverage containers cut into stars shapes, evoking the way he decorated his living space. Around the corner, sculptures of trout, carved from Styrofoam coolers abandoned on the beach, almost leap out of their shadow box frames.

Turn the corner and you come across the biggest reveal. A master recycler of materials, Voronovsky executed most of his paintings on cardboard, using bright paints he acquired at the local Woolworth five-and-dime. In one case, he painted a lakeside scene of birds alighting on a fence, an idyll of the artist’s fondly remembered life in Ukraine – and typical Voronovsky fare. But, on the other side of the double-sided frame, you will see the canvas for what it is – a Pizza Hut takeout box, grease stains and all. The late-’70s graphic imprint reads, “Let Yourself Go to Pizza Hut,” as convincing a call to indulge in fast-food America as any.

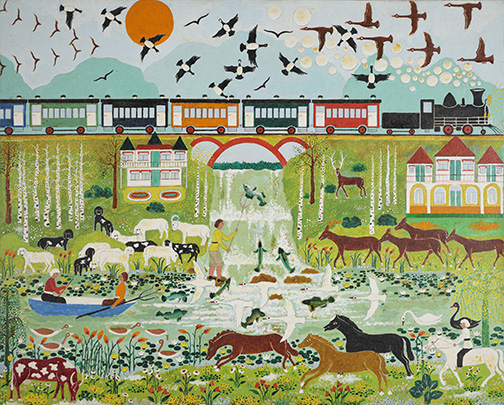

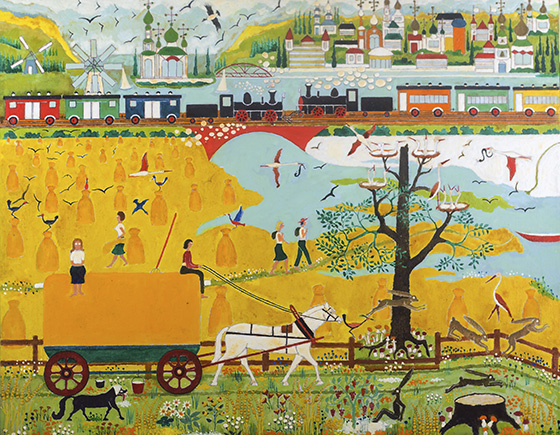

When taken in the context of Voronovsky’s life, all of this food – so brightly packaged and aggressively marketed – takes on new meaning. Born in 1903 in eastern Ukraine, Voronvosky grew up in a middle-class family and went to school to study music. From what he told the people later in his life, these were the happiest of days. This time spent roaming through forests in search of mushrooms, fishing for trout on the rivers, and walking hand-in-hand through wheat fields are the building blocks of Voronovsky’s art. They are constructed out of rosy memories and elevated into colorful celebrations of folk life, both through a remarkable fluency in craft traditions and an unbridled imagination. These scenes portray Ukraine as fertile and verdant; it is not by accident that the country earned the moniker “The Breadbasket of Europe.”

These Memoryscapes were selected from a bank that no doubt included many unhappy memories. Like so many of his Eastern European contemporaries who eventually made their way to the United States, Voronvosky’s life is both archetypal and extraordinary. The first half of the 20th century was a succession of violent encounters between people and politics that killed millions and displaced millions more. With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, and the subsequent revolution in Russia, Ukraine passed from a region of the Tsar’s empire to a republic of the newly established Soviet Union. The first in a series of famines ensued.

While Ukraine benefited from a kind of “affirmative action empire” in the early 1920s – promoting Ukrainian culture and individuals to positions of power – by 1928, with the introduction of Stalin’s first Five Year Plan, the perks quickly disappeared. Collectivization – and a seven-day work week – was forced on peasants who had for generations owned and worked their own farmland. Famine struck almost instantly, killing thousands. Four years later, however, things would get much worse. In an effort to eradicate Ukrainian nationalist groups, Stalin – by requisitioning grain and withholding aid – engineered a famine that killed almost four million Ukrainians. This was a genocide on an unprecedented scale.

Less than a decade later, the Second World War broke out, and with Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, Ukraine was both a battleground between armies and a killing field for the genocidal policies of both Stalin and Hitler. Food, it goes without saying, was often hard to come by.

We know little about how Voronovsky experienced this period of his life. A trove of materials accumulated throughout his life, containing hundreds of letters, photographs, and legal documents dating from the 1930s through to the ‘80s was preserved by Gary Monroe. This valuable material helps us establish some key dates of Voronovsky’s life story.

Further mentions of Voronovsky show up in archives in America and Europe, proof of his multiple migrations. We find that in 1933 he married a woman in Kyiv, Johanna Adamec, with whom he would have two children. That he was in the city during the Holodomor, the genocidal famine of 1932-33, probably means that he was shielded from the worst of the hunger. In a reversal of most periods of food scarcity, it was the countryside, not the cities, that starved.

We also know that Voronovsky was in Kyiv in 1941 when the Nazi forces took the city, but he does not resurface in records until late Summer of 1944. He is documented with his family in a Nazi resettlement camp – Voronovsky was Orthodox Christian, not Jewish – in Soldau (modern day Poland). From there, he and his family were transferred to Prague, though Voronovsky was soon separated from them and converted into a forced laborer. He would never see his family again.

From this point on, Voronovsky’s life story comes more clearly into focus. After 1945, when his labor camp was liberated by Allied forces, Voronovsky lived in a Displaced Persons camp, large ad hoc communities of refugees awaiting repatriation, and later, resettlement. Staying in Camp Lysenko, along with many other Ukrainian refugees, Voronovsky participated in a rich cultural and social life, performing as a musician in a traveling Ukrainian folk-dance troupe called the Musical Wanderers.

In 1951, with the assistance of international and American aid organizations, Voronovsky immigrated to the United States, working for a few months as a dishwasher in New York and quickly moving on to Philadelphia. Finding work in the rail industry, Voronovsky lived for the next 20 years in the already large Ukrainian community in the city.

Voronvosky was a restless soul, however. Almost immediately upon arriving in Philadelphia, he started taking the bus and the train to destinations up and down the Eastern Seaboard. By the late 1950s, he had stumbled on his New World paradise, Miami Beach. Traveling alone or with friends, Voronovsky made visits to the seaside resort throughout the late ‘50s and for all of the ‘60s.

When it came time to retire from the rail industry and take his pension, Voronovsky moved into Miami Beach’s Colony Hotel. One of the many historic Art Deco hotels lining South Beach, the Colony had been unofficially converted into long-term residencies for the city’s aging Eastern European population. Voronovsky turned his third-floor room into an “oasis of color and light,” an environment constructed from repurposed materials of the artist’s present as canvases for exploring his past.

All of which brings us back to food. Look closely at those images of Voronovsky in his brightly decorated room, and you will notice even more of the detritus of consumption: egg cartons, coffee tin lids, a crab’s carapace. Whereas back in Ukraine, folk customs relied on scavenging for natural materials – the practice of painting eggshells, called pysanky, naturally required eggshells to paint on. In Miami Beach, Voronovsky had to adapt to his environs, combing the beach for litter or re-purposing his empty soda cans.

This was doubtless making a virtue out of a necessity. Voronovsky was after all a pensioner living on his own. But it also reflected a broader vision of living and creating in a fractured world. After so many years of absence, Voronovsky knew how to preserve, transform, and make beautiful the little that remained. “I like to do decoration for my room from… what is throwen [sic] away,” he once wrote in English. Those egg cartons pinned to his walls were the Miami Beach equivalent to the pysanky he grew up painting in Ukraine, as un-wasteful as they are ornamental.

Even when his memories of Ukraine are not painted on pizza boxes or carved from a cooler, much of his artwork is still about food. Foraging for mushrooms was – and still is – an Eastern European tradition. Fishing for trout was a favorite pastime of Voronovsky’s, spearing fish along the rivers near the country houses of the Ukrainian middle and upper classes. Even his cityscapes are not without references to agriculture. Most of his view of Kyiv is given over to a representation of the rich soil of the Dnieper’s Left Bank, a landscape punctuated by a plenitude of hay bales.

Voronovsky also mined Slavic fairy tales in his art. As both painting and sculpture, Voronovsky rendered visual the fairy tale of the Giant Turnip, in which a grandfather recruits his entire family, and eventually the neighborhood animals, to wrest an over-sized root vegetable from the ground. The effort succeeds.

It is a tale that holds special resonance against the backdrop of collectivization in the late 1920s and ‘30s. Per Stalin’s orders, not even community or personal gardens were allowed to exist; everything was given over to the state. In his painting, the giant turnip is surrounded by a watermelon patch, small flowers growing in front of the cottages, and a fruit tree in full bloom. Additionally, the Left Bank farmland does not show industrial machines, as such collectivized farms were supposed to, but by a simple hay cart ridden by contented-looking peasants. Those chickens grazing in the forest, too, would likely have been confiscated. Having an animal during the worst times of the Holodomor was grounds for arrest, or worse.

Voronovsky’s images are not innocuous fantasies then. Even if he never wrote or spoke about his opposition to Soviet policies, his art is a testament to his resistance, not only by creating in the face of exceptional violence, but also by conjuring images that attest to the happiness of enjoying the simplest of freedoms.

KYLE MANCUSO is the Curatorial Research Associate at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta.

As seen in the Folk Art Messenger: